I live in the Desert Southwest, home to Los Alamos and White Sands. Explosive images are burned into my psyche while unexploded ordnance and military debris litter the surrounding desert. Still, 79 years after Hiroshima, the threat of nuclear war looms. “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” So quickly have we forgotten the life of reason.

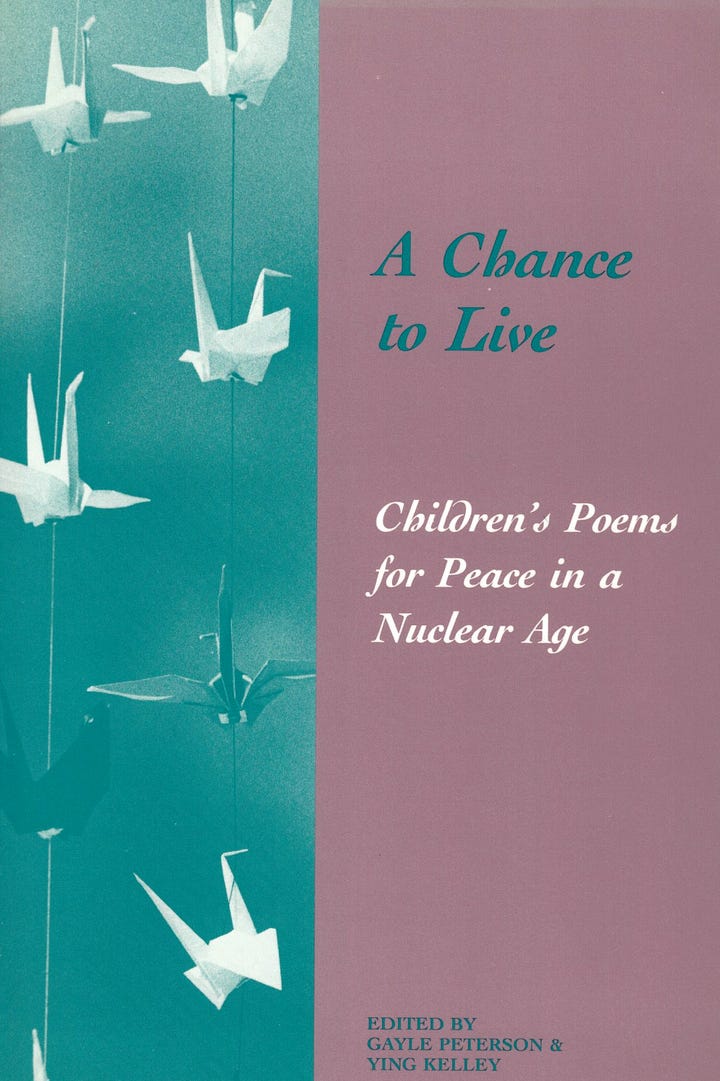

In 1985, while living in Miami, Florida, Mindbody Press presented me with a project. The small press in Berkeley, CA, had published a book of children’s artwork and poetry as part of a school unit on peace entitled A Chance to Live: Children’s Poems for Peace in a Nuclear Age. Active in the Peace Movement as a singer-songwriter, Mindbody asked me to put the children’s poetry to music for a combined book and cassette tape release.

Ecstatic to embark on a writing and recording project, I picked up my pen and guitar and began to compose. I sent a demo to the publisher, and they loved it. I booked a prominent Miami recording studio and hired friends to play on my first professional recording release.

The children who composed the poems and created the artwork attended the Berkeley Arts Magnet School. They were told the story of Sadako and the Thousand Cranes and how, in the spring of 1945, Sadako was sent to the Japanese countryside along with most children in the city of Hiroshima. She returned in search of her parents on the afternoon of August 6th. At that time, very few people knew about the effects of radiation. Before she died, however, Sadako prayed that no atomic bomb would ever again be dropped on the people of the world. She knew the crane’s legend and had often heard it said that if a person folded 1000 paper cranes, that a wish or a prayer would come true. She managed to fold 688 before her fingers lost their hold on life.

On August 6th, a powerful tradition unfolds as thousands of folded paper cranes are brought to the peace parks for presentation. That initiative was taken up by the students at the Berkeley Arts Magnet School. They chose to complete the work that Sadako had begun and folded 2,500 paper cranes, which they presented to the Berkeley City Council. Their wish for world peace, stimulated by the horror of Hiroshima, overflowed into an abundance of poems and artwork. This project is a testament to their natural and spontaneous need to express their feelings. The poems and artwork are a reflection of their inner minds as they grapple with the concept of war, particularly nuclear war, and strive to communicate their desire for peace. A Chance to Live is a dedication to their future and the future of children everywhere.

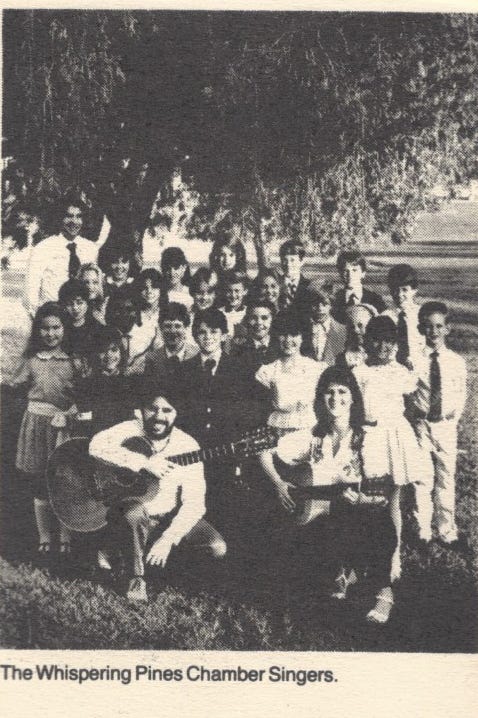

Meanwhile, back in Miami, I could hear children’s voices singing the poems I had arranged and put to music. It was children who had written the original words, after all. So, I searched for a children’s chorus and found the Whispering Pines Chamber Singers. Their choral director seemed open to the idea, so we arranged an audition. When I arrived at Whispering Pines Elementary School, a mother whose son sang in the chorus greeted me with a gorgeous clutch of colorful paper cranes strung together and hanging on a mobile. The mother, a Japanese woman from Okinawa excited about the project, had made the mobile and wanted to gift me with the cranes. I hugged her in gratitude, and we both cried. I took it as a sign. An entire ocean away from the children in California, children in Florida would lend their voices to what had become a bicoastal project.

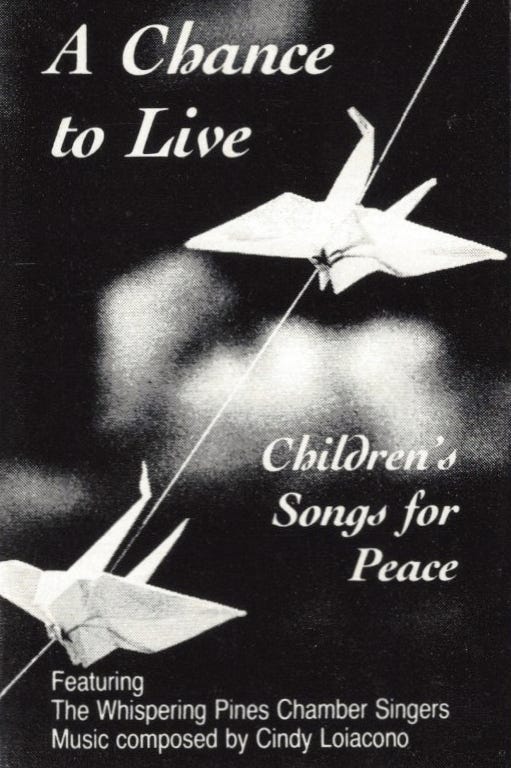

Then, I hired a professional photographer to shoot the cranes for the book and cassette cover. The cassette title is A Chance to Live: Children’s Songs for Peace. The project was endorsed and significantly strengthened by the support of anti-nuclear advocate Helen Caldicott, M.D., president of Physicians for Social Responsibility. Her endorsement added a layer of credibility and reassurance to the project. A Chance to Live was used in the national school system’s Teach Peace Project, making its way into libraries, schools, and children’s homes.

This is an extremely useful book for all parents to read because it is the children we must save and the children who feel totally betrayed by our psychic numbing and mindlessness when it comes to their future, and the thought of the prospect of nuclear war.

–Dr. Helen Caldicott, Pediatrician

The presence of nuclear arms in the world brings war home to our families, our children, and ourselves. Death by war is not new to the children of the third world, nor is it new to families who have lost loved ones in wars overseas. Yet this is the first time that children of all ages, races, and nationalities have been simultaneously presented with the possibility of global destruction.

To children who learn about dying through the destruction of war, death becomes synonymous with the unearthly, unerring denial of life. When children become afraid of death in the most basic sense, they become afraid of life. —Gayle Peterson, parent and A Chance to Live editor.

I am still attempting to understand war, particularly nuclear war, and am no different from the schoolchildren. I never thought all these years later we would still be having this conversation. A Chance to Live is what the children have to say about the world in which we live. Listen in a child’s tongue to what so many of us adults have not yet found the words to express. These children dare to visualize what few of us adults have the courage to imagine–a world in peace.

If There Were…

from A Chance to Live: Children’s Songs for Peace

A Teachers Story

by Carole Ono from A Chance to Live

Peace. How do we teach children about peace? What can we say or do as teachers that will truly give children the heart space to value peace? How can we structure lessons about something as intangible as nuclear war?

We just jumped in. We began by sharing the film “One Thousand Cranes: Children of Hiroshima” MacMillan Films, N.Y., 1968. We talked about the effects of radiation. We talked about children, and we talked about the act of folding paper cranes as a demonstration for peace.

Then followed a second film, “The Last Epidemic” Impact Films, Santa Cruz, CA, 1981. This film brought the consequences of nuclear warfare closer to home. We talked together of our fears, and of alternative ways to survive. And through discussion, the kids figured out that ending the nuclear arms race was the only solution. They concluded that peace was the only answer. They even began to think about ways to bring about a nuclear freeze based upon efforts of mutual trust and understanding. These kids are ten, eleven, and twelve-year olds!

Perhaps it is up to all of us to see that people everywhere have the chance to live, and to die as they choose.

Live to be Eighty

Original poem by Rabinder Khurana, 8th grade, arranged by Thea. Solo by Mathew Wright with Thea backing on guitar and vocals.

I am only 12 years old, I want to live to be eighty

I live in fear day to day, I don’t think war’s the way

The people say you can survive, they may be right

but you would starve, the food, the water, would be contaminated

if you eat it or drink it you’d be mutated

I’d rather die than have nine eyes

Every night after all my work

I lie on my bed

And think of war, not guns or tanks, but nuclear bombs

Paid Subscribers receive premium content below

A Chance to Live is currently out of print, but I would like to share the following songs from A Chance to Live: Children’s Songs for Peace with my paid subscribers: Little Ones, Cranes, Feathers in the Wind, and 1000 Cranes

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thea Summer Deer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.