The Seminole Indian Village lives as my earliest and most primal memory where everything is sound, and light, and color: The Seminole language, exotic birds calling from sun-drenched trees, warm palm-frond rustling wind, howling monkeys, the peacocks piercing cry like wailing babies, the Macaws earsplitting shriek. There is the constant clicking of a manual Singer sewing machine, measuring time against the assemblage of colorful cotton cloth into Seminole piecework beneath weathered, dark-skinned hands. The dank and rancid odor from the smoldering cooking fires is the most pervasive and permeates everything.

I didn’t live in the Musa Isle Indian Village, but at The Village in a white man’s house that sat opposite the tourist attraction at the main entrance. We lived in a house that withstood hurricanes, while the Indians lived in a chickee hut that would likely blow away. The Indian kids played in the dirt with bottle caps, sticks, and paper cups. I had a swimming pool, a surrey with the fringe on top, a pony, a playhouse, a swing set, and a zip line. The contrast between the Red and White Nations conflicted me.

Too young to understand race inequality, or atrocities committed in the name of white man’s money, god, or greed, I ran unfettered and uninvited into the Indian world. But they had to be invited into mine. It confounded me. My parents toxic beliefs and attitude toward the Indians poisoned my world like an octopus dying in a glass tank, poisoned by its ink.

Musa Isle was formed between the Miami River’s north and south forks when still a wild river. The Seminoles traveled down it from the Everglades, camping along its banks and establishing the famous Musa Isle Village and Trading Post. Musa Isle, meaning “island of bananas” in the Seminole language, is named for the abundance of bananas that grow there. After white men finished buying up the land adjacent to the river, they employed the Indians in what became a long-term relationship between the Seminoles and tourism.

Mom purchased The Village and its forty acres of prime waterfront on the Miami River, from her parents, John A. and Nellie Campbell, in 1955. I was born that same year. In 1964 after running The Village as a tourist attraction for almost a decade, my parents, Alice and George Stacey, closed it for good, and we moved away.

By white law, my parents owned the land upon which the Indians lived. But the Seminoles didn’t believe in private land ownership. In their view, the land belonged to everyone, and everyone belonged to the land. My parents ultimately controlled their destiny if such a thing were possible. The fires of resentment smoldered and had been, and would be, for a long time.

After The Village sold, it took a full year of painstaking effort and heartbreak to relocate all the families who had lived there for generations: the Billys, Oceolas, Tigers, and Jims, to the desolate Tamiami Trail in the Everglades. The animals also had to be relocated; flamingos, monkeys, various rare birds, an entire alligator and crocodile farm, the ocelot, and the otter, all sold away down the river.

After the white man had dammed the river and drained the Everglades, the Indians could no longer bring pelts and plumes to the Musa Isle trading post in their boats. They became forced to leave the Everglades, move into the tourist attraction village, and embrace the new tourism economy. When forced to relocate back to the Everglades and onto the reservation after the sale of Musa Isle, they lost a way of life for a second time.

Once they had relocated, the Seminoles reconstructed a tourist attraction, setting up a business as before by selling their crafts and wrestling alligators for gawking tourists. But their traditional lifestyle vanished. In the Everglades, the Seminoles no longer dwelt in hand-built chickees as they had done at Musa Isle. They did not live within the new tourist attraction at all. Instead, they commuted to put on a daily show for the tourists, returning to concrete houses much less likely to blow away.

Musa Isle Musings is an excerpt from my memoir in progress. Consider a $5 monthly subscription to support my continued writing and all the content I provide.

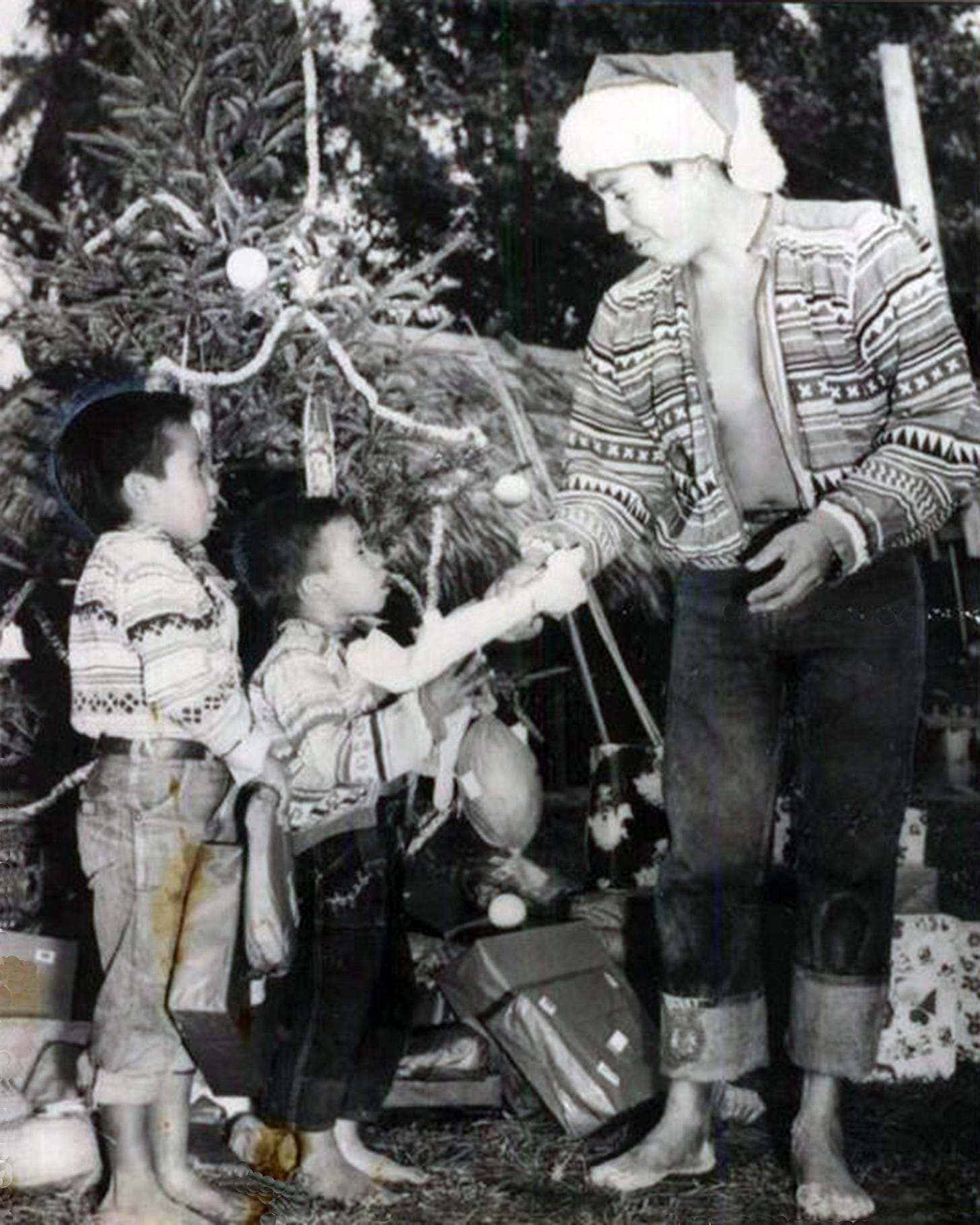

Premium content for paid subscribers below includes a gallery of additional Musa Isle photos from the Stacey Family Archives. The HistoryMiami museum houses items of historical interest from The Musa Isle Indian Village. My mother, Alice Stacey, donated these items and her voice narrated the exhibit.

The song, Two Roads, is also included and expresses my feelings about walking between two worlds. You can purchase Two Roads for download at Thea & the GreenMan. Released on My Mother’s Garden, it features Chuck, aka the GreenMan, Willhide, and 2x grammy winner Mary Youngblood.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thea Summer Deer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.