Caring for leather is a simple act. One that connects me to sustainable practices and things that last. The smell of mink oil applied to a soft cloth rag, passing over burnished leather beneath weathered hands, tells a story.

The ring of a horse’s bridle leads me from the stall, supple leather reins in hand. The creak of the saddle groans with a longing for the American West. The smell of Spanish leather sails me far across the sea. I have known all these things.

Taking care of leather and appreciating its durability unites me with the spirit of the four-legged animal whose coat I wear. I need to feel the warm animal nature of my own skin, which is not as durable as the spirit that endures. Leather has a soul.

Natural oils will replenish my tanned leather hides and preserve and darken its color. I reflect on my “old bag of bones,” or “skin bag,” the elders call the skin we live in. Every morning, I put oil on my skin. My mother taught me this. Part of her daily bathing ritual, it is now a part of mine. I observe myself in the antique bathroom mirror as fingertips massage rose otto-laced emu oil into aging lines, determined to stay present with myself as I shapeshift through time.

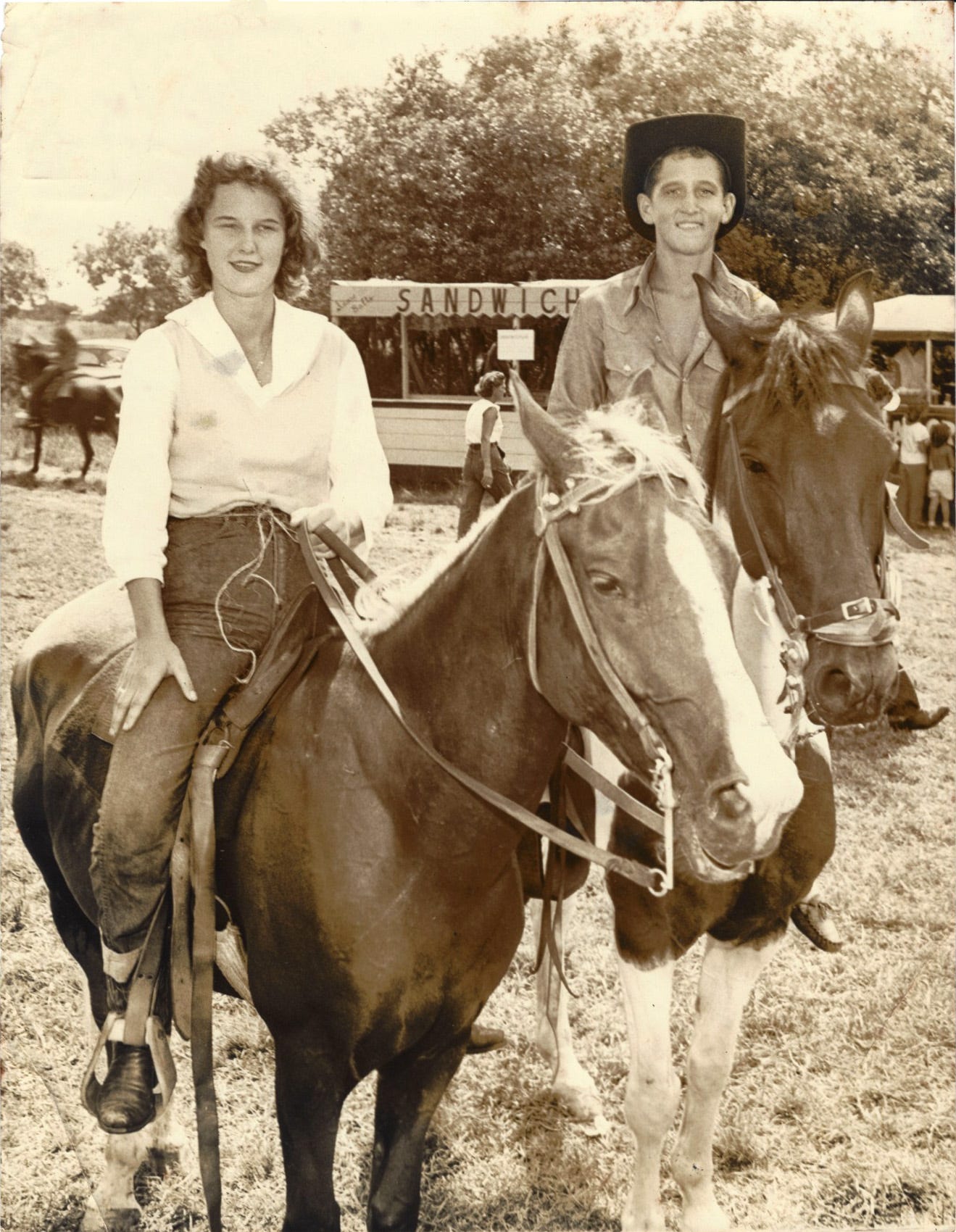

Leather is nostalgia. The hours I have spent cleaning and oiling saddles and bridles taught me to love the smell of horse sweat and leather. It is a love affair that began as a young girl riding into the sunset, singing old cowboy songs.

When I die, take my saddle from the wall, put it on my pony and lead him from his stall, tie my bones to his back, turn our faces to the west, and we’ll ride the prairie that we love the best.

— original poem by Carl Sandburg, a traditional American cowboy song (I Ride an Ol’ Paint) found through the western poets of Santa Fe. The song came to them from a cowboy who was last heard of heading for the Mexican border. Sandburg described the song as one of a man in harmony with the values of the American West. Western Writers of America chose it as one of the top 100 Western songs of all time.

As an adult, I skinned and tanned snake, rabbit, skunk, and deer. I collected beaver, coyote, fox, and wolf pelts. Working with leather felt like an initiation into the give-a-way tribe of animals whose spiritual Medicine I needed to learn. My hands touching animal skin transports me to an earlier time and an ageless wisdom.

Like most well-made things, leather can last a lifetime if you care for it. When leather goes back to earth, it creates life giving soil, unlike synthetic leather that ends up in landfills. Synthetics have become the mainstay of a throwaway society and may take hundreds of year to decay. Faux leather begins with a fabric base such as polyester and a plastic coating made from polyvinyl chloride (PVC).

Polyester made from petroleum byproducts is an endocrine disruptor. Xenoestrogens, widely diffused in our environment and food supply, are sourced from plastic. They can be found in breast milk and the flame retardant polyester pajamas toddlers are required to wear “for their own good,” according to US regulations. Polyester is not eco-friendly and ends up in our waterways as microplastics that are ingested by fish, other marine life, and eventually people. Xenoestrogens can cause cancer and lead to deleterious effects that potentiate a variety of neurological diseases.

In the 1970s, in my late teens and early twenties, I worked in a leather shop making custom leather goods for Karen, a friend who later went to school to become a saddlemaker. I witnessed her hands double in size from pulling and stretching leather over saddle trees made from wood. I stitched purses, tooled and dyed belts in her shop, and mended gun holsters, bridles, and the occasional saddle. I reminisce about an era when quality, handmade leather moccasins, shoes, and boots could still be easily found and purchased — shoes you resoled and wore for a lifetime.

I grew up with leather crafts made and sold at the Musa Isle Indian Village, where I lived and ran barefoot as a child. Then, hippies brought back the popularity of leather, fur, and suede. As a hippy, I wore leather-soled shoes that let my feet breathe and connect with the earth. The old ones have always known that bodily contact with the earth’s natural electric charge stabilizes physiology at the deepest levels, reducing inflammation and pain.

But then something happened. We stopped caring for leather. Due to the Industrial Revolution, skilled cobblers largely stopped making handmade leather boots around the late 19th century. A cobbler’s primary role today is to repair shoes, not create them. And they are few and far between — a dying breed. We not only throw away our synthetic shoes and boots but also our pride. Taking care of leather is a lesson in humility where we trade poisoning the environment for the sake of our pocket book or short term convenience for a long term vision of sustainability.

Unfortunately, we as a species seem to live in a dominator hierarchy that legitimizes exploitation. It is a hunt-it-down-and-kill-it mentality without thought for the honorable and respectful way to take the life of an animal who gives us our sustenance. We have forgotten that there are natural hierarchies based on mutual benefit. An example of a natural hierarchy is a child and their parent. But even our most formative relationships are threatened by dominator hierarchies, their agendas, and ideologies.

We also stopped caring for leather when the non-profit organization PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), founded in 1980, exposed how inhumane humans can be to animals. What started as a noble cause became another “cancel culture” movement long before the term became popularized.

PETA’s vegetarian British founder, Ingrid Newkirk, who was raised in a convent and became an atheist, studied to become a stockbroker before choosing animal protection as her career. In 2020, PETA put up billboards saying “Go leather-free.” PETA opposes the abuse of animals in any way, such as for food and clothing. Every week, Newkirk holds what The New Yorker calls a “war council” with her top strategists to plan aggressive media campaigns backed by a solid base of celebrity support. While many of the campaigns focus on large corporations and consumer boycotts, which have resulted in extensive and needed positive change, the rising fervor to reduce animal cruelty has become yet another orthodoxy and ideology seeking to change the names of cities like Fishkill, NY.

There is no question that animal abuse must cease. But what is seen by certain people around the world as necessary killing done in a sacred manner is not necessarily a commonly held view. Nor is the view that we are both creators and destroyers who give and take life. That view held by certain orthodoxies remains reserved for an invisible god who lives in a world other than this one and requires a mediator in the form of a priest. It is not a vision of sovereignty, sustainability, or personal empowerment. The way I see it, if we hadn’t lost our connection to the animals in the first place, we wouldn’t be in this conundrum. Honoring life and understanding the sacred relationship between taking a life and the life it gives us is how we have lived and survived on this planet until now.

A fundamentalist movement such as PETA becomes dangerous when people are pitted against each other and policed for non-conformity. In 2015, PETA sued British nature photographer David Slater, arguing that the monkey, whom they named Naruto, was entitled to the copyright of a selfie it had taken while handling Slater’s camera. The Court of Appeals favored Slater, saying that “PETA’s real motivation in this case was to advance its interests, not Naruto’s.” The court also wrote, "Puzzlingly, while representing to the world that 'animals are not ours to eat, wear, experiment on, use for entertainment, or abuse in any other way,' PETA seems to employ Naruto as an unwitting pawn in its ideological goals."

If PETA had its way, we would all be vegans and free from all animal-derived products. As a midwife and health advocate, I have seen first-hand the damage these diets cause in both the short and long term.

Newkirk, outspoken in her support of direct action, writes that no movement for social change has ever succeeded without what she calls the militarism component, saying, “Thinkers may prepare revolutions, but bandits must carry them out.” That is hardly a foundation upon which to build world peace.

The very same mindset that made the Holocaust possible, that we can do anything we want to those we decide are different or inferior, is what allows us to commit atrocities against animals every single day. —Matt Prescott

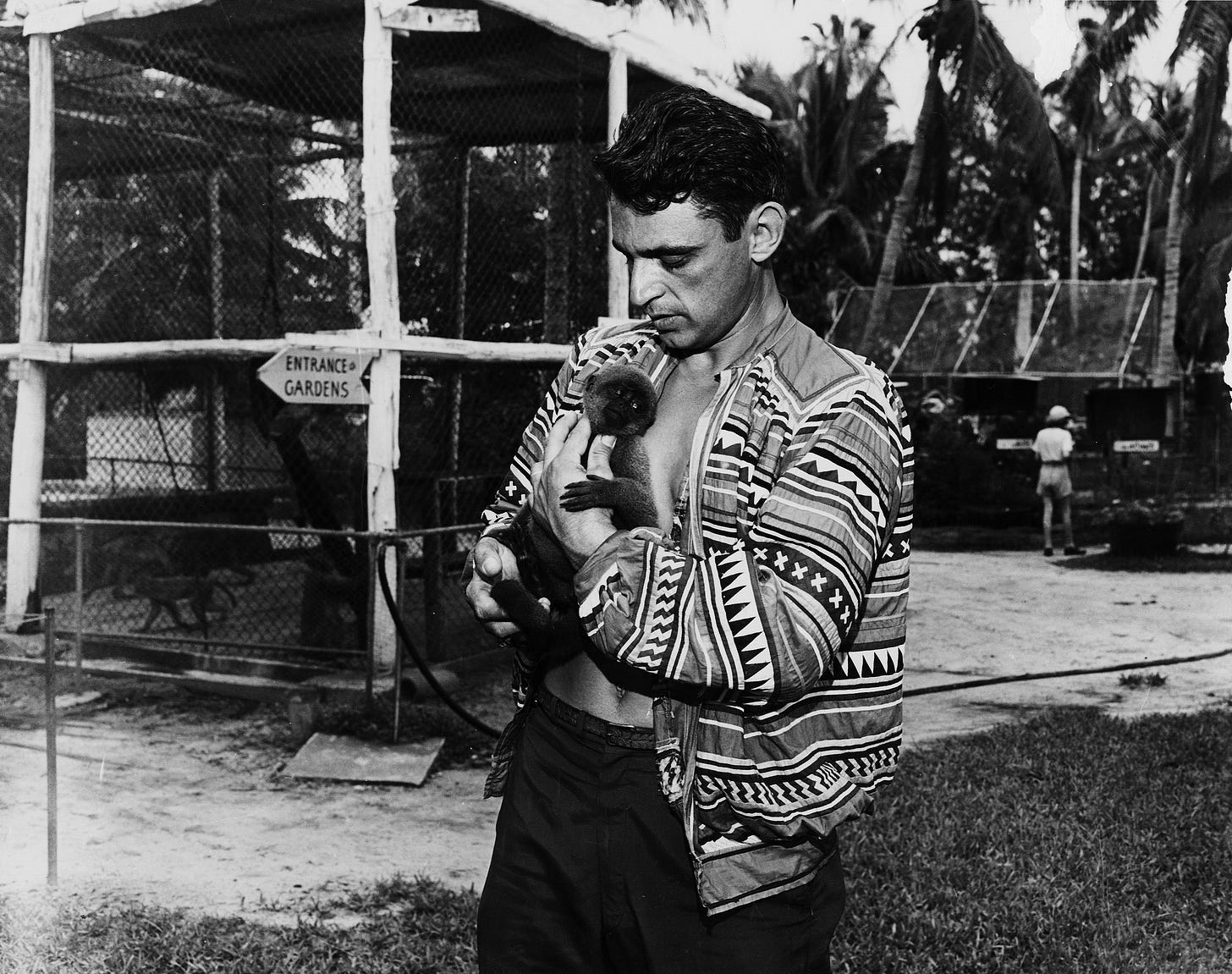

The Musa Isle Indian Village and Alligator Farm, where I lived as a child, also boasted a zoo that housed flamingos, ocelots, rare birds, monkeys, and more. Because of this, my dad made good friends with many other business owners involved in the tourism industry centered around animals. These included the Monkey Jungle (Joseph Dumond), Parrot Jungle (Franz Scherr), Rare Bird Farm (Alton Freeman), Miami Serpentarium (Bill Haast), and the Miami Seaquarium (R. Buckminster Fuller). That afforded me a unique opportunity to hang out with exotic animals and develop animal communication skills. And being a wild child, anytime I got out of line, Dad threatened to tan my hide with his leather belt. Something that unfortunately did happen on occasion.

I have so little leather left these days: a hand-tooled guitar strap my guitars have worn for nearly fifty years, some leather cowboy boots, and a black leather jacket from Spain. Most of the tanned hides and furs I have given away. But beneath those animal skins that ensured our survival through interminable winters, is humanity’s story and a history tied up in leather. Have we become so successful as a species that we no longer depend on the animals, declaring them useful or pests? So successful that we have brought them to extinction? We are not above the same natural laws that guarantee our extinction.

One day, as I was working in the yard of my 100-year-old farmhouse, I observed my neighbor target practicing with his bow. I have shot a recurve bow since I was a girl and shot a compound bow on a bow hunting league as an adult. So, I approached him and struck up a conversation.

“You goin’ bow hunting?” I asked.

“Yup,” he responded. “But I didn’t get a deer last year.”

“What do you do with the cape when you get one?” I queried.

“Well, most of the time, I just leave it. It’s too much to pack out,” my neighbor responded in his thick Appalachian drawl. For generations, his family had hunted turkey, deer, and bear in those hills.

I knew it could bring bad luck not to honor all parts of the animal. In addition to the meat, the cape makes for some fine deer hide, the skull mounted is an artistic trophy, and a craftsperson can make rattles from black deer toes. In the tradition I follow, you hunt a deer to bring back to a woman – your wife or your mother so she can feed the tribe. Only women can protect a hunter. The women made hunting and war shields to circumvent the male ego and keep the warrior humble. A deer will give itself away to a worthy hunter.

I didn’t know my Appalachian neighbor all that well, but I ventured to make him an offer because of my close-held beliefs.

"Well, if you promise to bring that cape back to me, I'll flesh it out. And I'd be willing to bet that will increase your chances of getting a deer this year."

He looked at me kinda strange, titled his head to the side, and said, “Well, alright.”

A few weeks later, at 2 a.m. on a freezing Autumn night, I woke to a pounding on my farmhouse door. What the hell, I thought. When I opened the door, my neighbor stood there with an ice cooler. In the cooler was one freshly skinned cape.

“Thanks,” he said. “Looks like you were right.”

“Looks like you kept your promise,” I grinned, half asleep.

“Good luck with that one,” he said. And off he went.

The bloody hide wouldn’t wait, so I grabbed my Buck Knife and went to work. It was full of ticks, and the night was freezing cold. I could barely feel my hands. But I honored that hunter, and I honored that hide. I didn’t do a perfect job and managed to nick it a time or two, but I took it to a taxidermist after I had fleshed it out, who tanned it with the hair on, and it made a beautiful hide that I carried with me for years.

Our greed and lack of consideration for what we destroy, the fellow creatures on our planet, will leave us dying “from a great loneliness of spirit.” The wholesale slaughter of animals whose parts we throw away and no longer use in a sacred manner as our ancestors once did serves as a reminder of what was, can never be again, and what may yet still return. Perhaps it is not too late to forge a new alliance that considers the next seven generations and what it means to be living in skin.

If all the beasts were gone, men would die from a great loneliness of spirit, for whatever happens to the beasts also happens to the man. All things are connected. Whatever befalls the Earth befalls the sons of the Earth. —Chief Seattle

Paid Subscribers receive the following premium content below:

Silence of the Bears by Thea. Performed live by Thea & The GreenMan, Unreleased.

Forest Heartbeat Drum, photo of Thea by the late Marion Z. Skydancer, previously unpublished.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thea Summer Deer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.