Where does the Wolf sleep? In a canyon bend of memory, in the deep forest time beyond-time, when Wolf began as essence, her soul a shooting star of wildness, her lean body riding her spirit in from the Other Side, onto the Earth, into the Dream.

— Annie Woods

A howling commenced beyond my farmhouse door. The past few days had been Appalachian grey and cold. Good days for dying, I suppose. Washee howled for the runt of the litter I had taken from the fur-lined cedar den where she had recently given birth. The Littlest Wolf lay in a box, wrapped in a towel, on the hardwood floor in front of a warm and glowing wood stove.

The runt looked more wolfy than the others. I had taken notice. He had golden eyes, thick lanolin-rich fur, and a black v-shaped marking on his tail like Washee. I brought him into the house when he fell sick for closer observation. I prayed that he might live.

Washee is a Dakota name meaning “little chubby girl.” My wolf-hybrid greatly resembled that, although, in truth, it was her luxurious silver-grey fur coat that gave her that appearance. She is the second hybrid I have bred.

After leaving the Sonoran Desert, I never thought I would be a breeder of wolf-hybrids again until Washee came along. The pain of losing my last female and companion had made me ready to move on to other things. But when I moved to Highlands, North Carolina, and purchased a home with land surrounded by National Forest where a dog could romp and enjoy a good life, I found myself longing for the companionship of a four-legged friend.

The couple who owned Washee gave her to me when she was six months old. They had relocated to Western North Carolina from Wisconsin, where they bred and trained sled dogs. They chose Washee to be in training as the head of their sled dog team. Their new business adventure, however, running a gem mine near a busy scenic highway, proved more demanding than anticipated. They no longer had enough time for their dogs or a safe enough place to let them run. When a flyer circulated across my desk with a photo of Washee, I fell in love at first sight. Incredibly beautiful, she was also exceptionally well trained.

By the time Washee turned two, she had gone into heat twice. Twice I met with scheduling conflicts and canceled appointments to have her spayed. My neighbor owned a Great Pyrenees-wolf hybrid named Ziggy and wanted to breed him to Washee. Friends who knew these animals thought it would be a fabulous mix. A mutual friend visiting from California, Stephen Longfellow Fiske, had also met Ziggy and Washee. The two wolf-hybrids had similar personalities, well-natured, loving, and intelligent.

Stephen is a fellow singer-songwriter and descendant of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He loved the animals so much that he offered to drive back to North Carolina from California for a pup if we decided to breed. So we did, and he did.

Ziggy and Washee spent two days together when Washee went into her third heat. Bred the first week in January, I felt concerned about the pups being born before Springtime. Wolves gestate for about two months and generally give birth in April or May. That put Washee a month early. I consoled myself in the knowledge that these are northern dogs acclimated to 40 degrees below zero temps. Washee would do just fine. She had a comfortable pen lined with straw and a large doghouse lined with cedar shavings.

One Saturday afternoon, I could see that Washee had gone into labor when she started nervously pacing in her pen. Half an hour before sunset, she howled an unrelenting long and mournful cry until I went to be with her, crawling into the doghouse at her insistence. She began to settle down then, concentrating on her labor. I felt somewhat fearful that she could decide in her discomfort that I had intruded on her space and would turn on me. But she only lay across my lap and wanted to be stroked and soothed while I spoke to her softly, encouragingly.

The last glow of daylight filtered through the doghouse doorway as the sun began to set and cast a dim halo of light around Washee. She became the wolf mother, primal and wild. Her power awed me as she allowed my witnessing of the birth. Although I had been a midwife and witnessed many births, nothing compared to that moment of being invited into the den of a laboring wolf dog.

After the first pup emerged, Washee left it with the cord intact. She barely touched it until after birthing the second pup. They came about an hour apart. She worked hard laboring, panting, licking, and cleaning the newborns. Their cries emotionally moved me, sounding like a cross between a human newborn and a cat. I left around midnight after she had birthed five healthy pups, sore and exhausted from huddling in a cramped space with an 80-pound animal pressing against me.

I went to check on Washee in the morning and counted eight pups. She made it hard to get a nose count because she kept them so close, buried in her fur. Four days later, I discovered she had nine that included a runt. Washee had birthed eight males and one female. The runt was a male. When the weather turned frigid, she prepared a nest for them lined with the shedding of her furry undercoat.

The pups grew as babies do. They all seemed fat and healthy, even the runt. They stayed warm inside the doghouse with mama on snowy nights and temps below freezing. A few days shy of four weeks, they started eating puppy food and came out of the doghouse to romp and play. Four weeks to the day, I discovered the runt struggling to keep up with the others. I picked him up and smelled the acrid odor of an infection. Badly dehydrated, I suspected his bladder. While holding this wolfy-looking pup before, he had seemed fine. But he had grown weaker, and that is when I brought him into the farmhouse and administered water through a syringe. When I noticed blood in his urine, I picked up the phone and called the vet.

Living in a small mountain village has advantages. In Highlands, we had a dedicated veterinarian. She agreed to meet me at the clinic on a Friday night even though she was tired after a long week and long day at work. The prognosis wasn’t good. She believed his little system had begun to shut down and sent me home with antibiotics for the infection. She said I would know within two days if he would live or die.

With the help of my daughter’s boyfriend, we kept him in a box on a soft towel and nursed him around the clock for two days giving fluids on the hour, every hour. We even milked Washee to ensure that the Littlest Wolf would have everything he needed for a fighting chance. In the middle of the second night, he stopped being able to hold anything down. The boyfriend selflessly stayed up the entire night. By morning I knew the pup was dying.

I wept in the kitchen on that grey wintery day while gazing through French doors at the serene pasture behind the farmhouse. I wrote a poem. My daughter came down from upstairs and hugged me.

We returned the Littlest Wolf to his brothers, sister, and mother, where he felt comfortable and familiar. Late that afternoon, we brought him back inside, and I tried to give him one more dose of antibiotics, which he vomited. After that, I could hear fluid rattling in his lungs when he breathed. I sat with him through the evening, comforting him when he woke. He grew weaker by the hour.

The boyfriend, who had selflessly stayed up the previous night nursing the pup, now said goodbye. “All puppies go to heaven,” he said. Then he offered to take the pup outside and quickly put it out of its misery. I thought, this is the difference between a boy and a man. I admired the noble offer and his selfless care and courage but declined. I wanted this baby to die as peacefully as possible. The boyfriend didn’t think he would make it until morning. And he was right.

At 10:50 pm that night, the Littlest Wolf died. He struggled twice as I gently held my hand on him, then basically gave up and convulsed with his last breaths. With that last breath, the pup threw back his head, and his ears stood straight up. At that moment, he looked like a perfect little wolf. Perfect on the outside, but something hadn’t been quite right on the inside.

We covered him with the towel in the box where he died and in my moment of grief, I knew this little pup was no great loss and only nature taking its course. But the feeling of loss had connected to other losses. I would bury him in the morning.

The next day dawned bright and cold, crisp with newly fallen snow. I stuffed some tobacco in my denim shirt top pocket, snapped it close, and put on my jacket, gloves, boots, and cap. Then I put the dead baby wrapped up in the towel and a hand shovel in my backpack and headed out into the woods. There, I sensed the presence of a bear, told earlier in the week by a neighbor that they were already out of hibernation. I stopped and listened. In front of me stood an old forking tree, the two that meet the one.

I dropped to my knees beneath the tree and started clawing like a bear in the frozen ground, its spirit moving in me. My effort yielded a perfect bed: the depth and shape of the pup. I unwrapped the body one last time to say goodbye, surprised to see the ears still standing up, a perfect little wolf. His body felt cold and the tobacco warm when I took it from my breast pocket. I addressed the spirits living in those woods as I sprinkled tobacco over him and made prayers to the four directions. I called to the crows to come and help take his little spirit home. I asked the tree to protect him while his body returned to the Earth.

His spirit will run free now through the woods as wolves are meant to run, I thought to myself as the wind blew whispers to my ears. And then I heard his spirit speak -

The time of the wolf is coming to an end. I cannot stay here anymore. There will be no wild world left for wild things like me to run free.

Grief washed over me more powerfully than any personal loss I had known. I saw the death of the Littlest Wolf as a symbol of something greater passing away into yet another world. I don’t understand how we collectively grieve for such a thing. I asked him to hold a place for me in that other world. The wolf is the pathfinder, the teacher in this world or the next. I had followed them and would follow them still.

Standing on the ridge, looking back on the tree beneath which the Littlest Wolf lay, I could see that it stood taller than the rest. Above the mantle of pure white snow, the sky began to clear. Crows called from their hidden places across the forest, answering my prayers. I knew Washee waited as I turned and walked away.

Return of the Wolves

by Duane Niatum

All through the valley, the people are whispering:

the wolves are returning, returning

to the narrow edge of our fields, our dreams.

They are returning the cold to us.

They are wearing the crowns of ambush,

offering the rank and beautiful snow-shapes

of dead sheep, an old man too deep in his cups,

the trapper’s gnawed hands, the hunter’s tongue.

They are returning the whispers of our lovers,

whose promises are less enduring than the wolves.

Their teeth are carving the sky into delicate antlers,

carving dark totems full of moose dreams: meadows

where light grows with the marshgrass and water

is a dark wolf under the hoof.

Their teeth are carving our children’s names

on every trail, carving night into a different bone -

one that seems to be part of my body’s long memory.

Their fur is gathering shadows, gathering

the thick-teethed white-boned howl of their tribe.

gathering the broken-deer smell of wind

into their longhouse of pine and denned earth,

gathering me also, from my farmhouse

with its golden light and empty rooms, to the cedar

that also howls its woody name to the cave of stars,

where I am silent as a bow unstrung

and my scars are not from loving wolves.

Duane Niatum is a Native American poet, author, and playwright from the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe in the Pacific Northwest, born to a Salish mother and Italian-American father. Having published numerous essays on Native American literature, he is one of the most influential promoters of Native American poetry. His own poetry has been translated into more than a dozen languages. Niatum has taught at numerous schools, colleges, and universities. Please support his work.

Recommended Documentary & Reading

Happy People: A Year in the Taiga, shows the beautiful relationship of a man to his sled dogs.

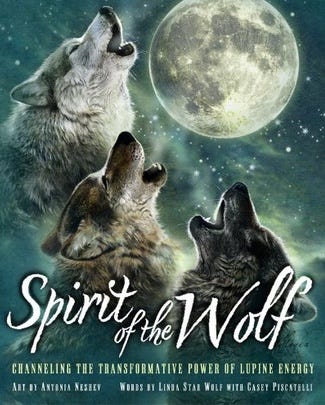

Spirit of the Wolf: Channeling the Transformative Power of Lupine Energy includes Wolf Tales essay by Thea Summer Deer, PDF download available for paid subscribers below.

If you wish to support wolves living in the wild, consider supporting the Voyageurs Wolf Project, which studies wolves and their prey in northern Minnesota.

Paid subscribers listen and receive a free download of the theme appropriate song, Wilderness of Rocks from Eagle’s Gift CD (featuring Heather ‘Lil’ Mama’ Hardy on violin, Stuart Munro (Sunyata) on electric and acoustic guitar, Amo Chip Dabny (Carlos Nakai Quartet) and Steve McCarty (Steve Miller Band) on background vocals)

And download a PDF of Thea’s Wolf Tales essay from Spirit of the Wolf below.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thea Summer Deer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.