When the Buffalo went away the hearts of my people fell to the ground, and they could not lift them up again. After this nothing happened. There was little singing anywhere. – Plenty Coups, Crow

The sun rose bright in Tucson, Arizona, that morning in 1992 when environmental psychologist and multimedia artist James Swan called and invited me to join the Buffalo Tour. It seemed like a dream. The tour’s headliners included Jerry Garcia, Maria Muldaur, and R. Carlos Nakai. Swan, who had organized the concert tour to raise money for tribal buffalo projects, offered what I hoped would be my lucky break. I signed the contract, and James sent me an America West plane ticket to the California kickoff concert. James’ non-profit, the Institute for the Study of Natural Systems, would sponsor the Buffalo Tour to restore buffalo on Indian lands and right a wrong done to the Native American peoples. But that dream collided with the American Indian Movement (AIM) when prominent AIM members on the non-profit’s board, including University of Colorado Prof. Vine Deloria Jr. and actor Floyd Red Crow Westerman, resigned. According to Swan, “They didn’t need or want white people putting Buffalo back on their land.”

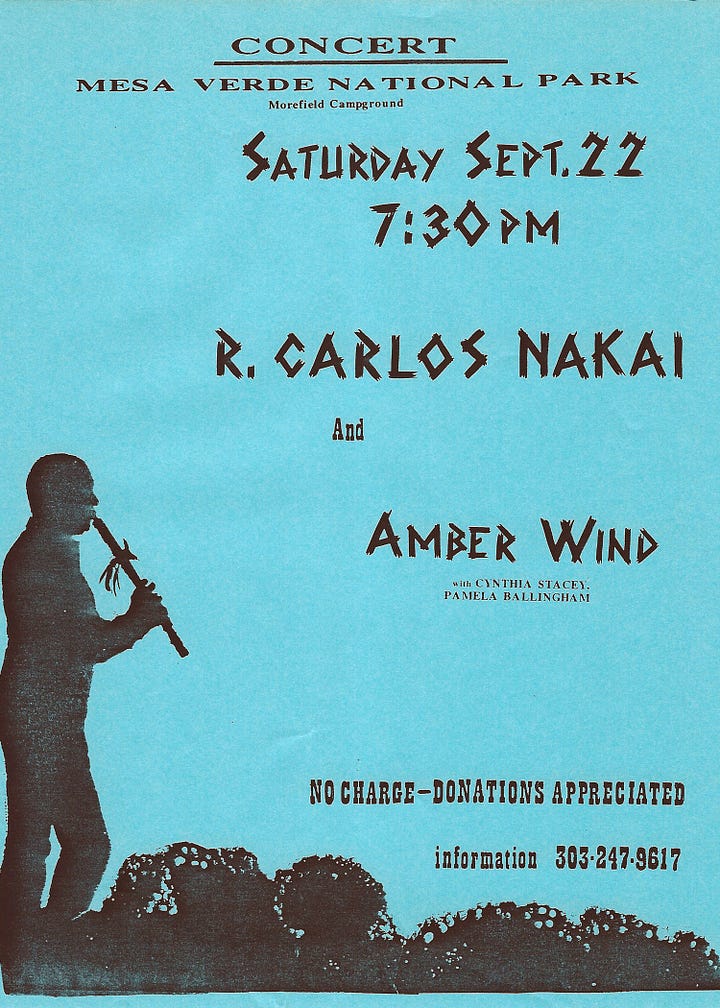

While living in San Francisco in the late 80s before moving to Tucson, I met James Swan and his wife, Roberta. Together, they produced the Spirit of Place Symposiums, which explored the relationship between ancient wisdom and modern science. James had written a book, Sacred Places: How the Living Earth Seeks Our Friendship. My duo, Amber Wind, performed at an earlier concert produced by the Swans in 1990, opening for R. Carlos Nakai at the Mesa Verde Symposium.

A few weeks before the Buffalo Tour kicked off in the spring of 1993, I received a distraught call from James Swan. Jerry Garcia, he informed me, was on the decline and had been taken to the hospital with an enlarged heart. He would be unable to perform. In a perfect storm, James had to cancel the Buffalo Tour. He had lost the support of the Native American community and his investment. Lawsuits ensued, and the far-reaching story hit the LA Times through the Associated Press. But the report didn’t tell the whole story. My hopes dashed, James told me to keep the plane ticket. As long as I traveled within the year before it expired, I could fly to any destination served by America West. I felt bitterly disappointed, but Spirit had other plans for me.

I spent the most down-and-out year following the tour’s cancellation in a tiny tin can trailer, smaller than a single wide, in a run-down Americanaville trailer park. One sweltering hot afternoon, holed up in the trailer with the air conditioner blasting, I stumbled across an ad for South by Southwest (SXSW), a music festival in Austin, Texas. That’s when I remembered the airline ticket from the canceled Buffalo Tour that was about to expire. I had always dreamed of going to SXSW and would only need to scrape a few hundred dollars together for the registration fee. So, I called the landlord and begged for mercy. Since my landlord was also a good friend, he generously offered to offset the rent so I could free up the funds. A few short weeks before the festival, I registered, and booked my flight, but I didn’t end up in Austin.

I met Annie Hawksong in 1989 when she came to do spiritual work at my healing retreat center in Tucson, traveling from Houston, Texas, where she lived. When I decided to go to Austin, I called, hoping to see her. Annie had also worked with Wolf Clan Seneca Elder Grandmother Twylah Nitsch. She was friends with Jamie Sams, who co-wrote Medicine Cards: The Discovery of Power Through the Ways of Animals, informed by Twylah. When the book came out, Annie sent me a signed copy. One of the Medicine Cards is Buffalo, the medicine of prayer and abundance. Twylah describes “Medicine” as anything deepening our connection to the Great Mystery and ourselves. A Buffalo Medicine person is someone willing to be the answer to someone else’s prayers. The abundance of Buffalo had blessed me with an airline ticket, but I did not yet know which prayer would be answered.

Texan by birth, Annie answered the phone in a Southern Texan drawl. She excitedly announced that she had a recording project underway with John York, formerly of The Byrds. Annie is also a singer-songwriter who wrote most of the songs for her album with York as a co-writer. She insisted I come to Houston and add my vocals to the mix, generously offering me a round-trip ticket from Austin to Houston. The timing of her recording session wasn’t good and would mean me skipping SXSW. I told her I would sleep on it.

Since everything connected to that airline ticket concerned furthering my music career, perhaps going to Houston would be more advantageous than staying in Austin. The following morning, I rolled some tobacco and consulted my spirit guides. Then, I called my spiritual counselor, Beverly Laughing Eagle, seeking her advice. She counseled me to take Annie up on her offer. It turned out to be good advice. The way I imagined it, the investment made to go to SXSW would come back to me in a different form. The decision had been difficult. But spirit nudged me toward Houston. Coincidentally, I also had two cousins in Houston I hadn’t seen in decades and planned to look them up.

The Austin-Bergstrom International Airport teemed with musicians from all over the world. In between flights, I became electrified with the spirit of Austin, declared “The Live Music Capital of the World.” Musicians vying for attention carried stringed instruments in their cases and made their way out of the airport as I made my way to the next gate. I was flying off to sing in one of Houston’s oldest and best studios. I had heard the call to adventure.

Annie treated me like a rock star, sending her driver, who she described as a “tall drink of water,” to pick me up at the Houston airport and bring me back to “Annie’s House.” After Annie’s grandmother passed away, she turned the big, beautiful house in an older upscale neighborhood into a haven for abused and battered women. Still reeling after a painful divorce from her prominent Houston attorney husband and losing custody of two sons, Annie saw it as a way to heal herself and as a way to give back. A work in progress, Annie’s House had no women in residence then, so we had the whole place to ourselves. The following morning, I woke to Annie sitting at the baby grand piano, her music gracing the spacious living room. I liked Annie’s music and would go on to record and release one of her songs on My Mother’s Garden. It is a song she wrote with John York called Hawk Song, and it is about healing the cycle of abuse passed down through the generations.

The recording session never happened. John York fell ill and canceled his flight at the last minute, so we had to postpone. But we still went to the studio, and Annie played me some of the tracks they had been working on. We both felt disappointed about the turn of events. Spirit kept nudging. Why had I forfeited SXSW? Why had Annie paid for my ticket to Houston? Why was I there?

With the recording studio session canceled, I now had time to see my cousins. Johnny sounded excited when I called and arranged for me, him, and his older sister, Shelley, to spend a day together on his boat. Johnny was the youngest of my two cousins on Mom’s side and the closest to me in age. We were both born in July, making us the same astrological sign of Cancer. He was wild and crazy, and I had a terrible crush on him as a teenager.

While cruising the waterways with my cousins, I felt drawn to Shelley. Flamboyant in her bikini, she talked loudly and liked to drink. Shelley, the best-dressed woman in the West, owned a classy cowgirl clothing store. Six years older than me, I looked up to her as a budding adolescent. She took me shopping at the Galleria when I was thirteen and helped me buy my first bra. But we were older now, and she seemed worn out and tired. Shelley had a child late in life with Steve, her third husband, a boy who was eight years old. She knew I liked music, so she and her husband offered to send their boy to an overnight babysitter on my last night in Houston and take me out for a late dinner at a club where their favorite band played. It sounded like fun at the time. They knew I had a plane to catch the next day, so they invited me to spend the night at their modern condo. I would see Annie at brunch before heading to the airport.

Steve drove us to the club and impressed me as sensible and steady. He dressed down compared to Shelley, wearing a short-sleeve, casual Oxford, khaki slacks, and sneakers. Steve had a degree in social work and worked with sexually abused and battered women, a recurring theme since arriving in Houston. Our conversation gravitated to what I had been through after the divorce from my children’s father and my move from Miami, Florida, to Berkley, California. I shared what the therapist in California had told me, “You are a classic case of sexual abuse.” But since I had no conscious memories, I didn’t know what to do with that other than create distance between myself and my family’s dysfunction.

The night wore on, and Shelley proceeded to get inebriated. The food tasted lousy, the band sucked, and I wasn’t having a good time. I felt like someone held hostage. I prayed to Great Spirit. Why was I there? There had to be a reason.

Shelley and Steve insisted on staying until closing time. I felt relieved to finally get in the car at one o’clock in the morning, with Steve as the designated driver, to go back to the condo. No sooner than we get in the car, Shelley turns to face me, reeking of alcohol.

“Honey, tell me more about your divorce,” she says, her speech slurred.

“What more do you want to know?” I tiredly replied, having already told her about losing custody.

“Whatever you want to tell me, “ she replies, looking straight into my eyes.

I surrender. “You know, I never did understand why my parents sided with my ex after I had been such a good mother. It practically killed me.”

Her eyes widened. “Oh, honey. You don’t know, do you?” She asked incredulously.

I didn’t miss a beat, “No,” I replied firmly, “but you will tell me.”

That question, “You don’t know, do you?” answered my prayer of why I was there. As an adoptee, it may not have told me who I was, where I came from, or to whom I belonged, but it gave me another piece of the puzzle. Shelley turned away to face forward again and quietly said, “I will tell you when we get home.”

You don’t stand a chance against my prayers. You don’t stand a chance against my love. — Robbie Robertson

When we returned to the condo, Steve made coffee, and Shelley sobered up a bit. He reassured me that he had done a lot of work with abused women and would hold space for us as he stepped out of the room. I waited in the bedroom while Shelley dressed for bed in the bathroom. She emerged wearing no panties beneath her flimsy nightgown. Then she came and sat on the floor at the foot of her bed and patted the rug for me to sit across from her. The dimly lit room felt eerie at two o’clock in the morning. I was wide awake, suspended in time.

When Shelley took my hands in hers and began to cry, I leaned in and wrapped her in my arms. Something inside of me shifted. What had started to unfold was no longer about me or what I needed to know. Somehow, I knew that Shelley needed to be regressed. I had seen it done many times, having been married to a hypnotherapist, and I had experienced hypnotic regression during my years of therapy. The situation felt so emotionally charged, that I shifted out of my emotions into facilitator mode.

Racking sobs shook Shelley’s exhausted body. Steve occasionally looked in on us, briefly cracking open the door, giving me a knowing nod, and quietly closing the door again. I pulled Shelley onto my lap like a vulnerable little girl and began to rock her.

“Shelley, where are you?” I asked softly.

“I’m – I’m in the bathroom,” she says, choking between sobs. “I’m in the bathroom of the house in Miami.”

I had old Polaroid photos of Shelley when she was a little girl taken at our home at the Indian Village in Miami before I was adopted. Her mother, Helen, raised two kids as a single mom in the ‘50s. She brought Shelley and her brother from Texas in the back of a station wagon to visit Mom, her older sister.

“What are you doing in the bathroom?” I ask.

“I’m taking a bath,” she says, her sobs increasing.

“Can you tell me what is happening right now?”

“George is lifting me. I don’t want him touching me. He is laying me on a towel on the floor,” she says, digging deeper into my lap.

George is my Dad. And Shelley couldn’t have been more than five years old.

“You are safe here now,” I reassure her.

Then, she curled up in a tight ball and started rocking herself. I kept reassuring her as I used hypnotic suggestions to take her deeper. And then she lost it.

“I’ll kill him! I’ll kill him! Get him away from me! I’m going to kill him,” she screamed repeatedly between howling cries.

Shelley thrashed out of my arms and off my lap and began convulsing on the floor. Steve peeked in to ensure we were okay, then quietly closed the door. I stood up, walked into the bathroom, turned on the cold water, and soaked a washcloth. Returning to the bedroom, I placed it gently on Shelley’s face, stroking her with the cool, wet cloth while calming and reassuring her with my voice. I coached her to breathe like I would a woman in labor. Then she passed out on the bedroom floor.

I lay beside Shelley, holding and spooning her and dozing in and out of consciousness until she stirred. Then I called Steve in and shared what had transpired. He said he knew she had been carrying some trauma like this, and was grateful to me for being there.

Shelley inviting me to sit on her bedroom floor had been no coincidence. My father had raped my cousin on the bathroom floor of my childhood home. Even after all these years, I can still see that haunted room.

When Shelley was ten, her mother, Helen, remarried. Her new husband, whom she married for life, was gentle, kind, and loving. Shelley would have been around eight when they first started dating and wouldn’t let her future stepfather touch or hug her. Shelley’s behavior seemed strange to them, and they eventually sought help. Through questioning, it emerged that she had been abused in some way by my father. She reported that my sister had also suffered at the hands of my father. I would have been around two years old at the time. When Granddaddy learned of this, he threatened to take his gun and kill my father.

“We will not lose a good man over a bad man,” my sensible grandmother said. She demanded that he take my father to court. And he did. But when the court put the girls on the witness stand, they became further traumatized and caused my grandparents to drop the charges. They were, after all, in the South in the 1950s. It served as a wake-up call for my father and whatever abuse I might have experienced before this stopped. I was three by that time.

I finally understood what the therapist had been saying when she said, “You are a classic case of sexual abuse.” I wasn’t crazy. I didn’t make it up. But my father did try to make it up to me for the rest of his life. I just didn’t know that was what he was doing until the canceled Buffalo Tour gave me a ticket to my destiny to see the truth.

Sexual abuse, along with the resulting loss of a sense of self, is costly. It cost Shelley her sobriety and her uterus to a hysterectomy shortly after giving birth to her son. She had a history of failed marriages, relationships, and businesses, as did I. The most significant difference is that Shelley doesn’t believe in “healing.” She stated, “Once something like this happens to you – you’re a done deal.” She called me “a done deal.” That is not what I believe.

I have continued to heal thanks to Shelley’s powerful and illuminating spotlight on my past. Things I never understood, like why Mom’s side of the family never had anything to do with Dad, why Mom remained in Miami, estranged from the rest of her family when they permanently settled in Texas, or why Mom’s mother wrote her out of the will among other things now make sense.

Johnny came that morning to pick Shelley and me up. Annie wanted us to meet her for brunch at the yacht club before my flight back to Tucson. When Johnny saw how exhausted we were from hardly any sleep, we told him what had transpired. He was supportive and expressed genuine concern.

Shelley wore sunglasses at brunch to hide her swollen eyes. The way Annie met Shelley and Johnny felt surreal. However, Annie was not a stranger to this story, and she offered extensive resources and referrals. Shelley wanted no part of it. She had been a victim in her mind, and that is how she would choose to remain, like bleached bones covering the Great Plains that buffalo had once darkened.

Less than 200 years ago, over 50 million buffalo roamed the plains in herds so thick that no one believed it would ever be possible to destroy all of them. By 1884, only a few hundred remained. We name cities and sports teams for them and put their likeness on flags, coins, and monuments. But in a few short years, technological advances were in the hands of people who didn’t know what they had, and an insatiable hunger for hides spelled doom for the iconic symbol of the American West. The first kill for a buffalo hunter was always the lead buffalo, a female cow. Hitting the leader confused the herd, kept them in one place longer, and extended the hunt. The meat was left to rot. No dignity, no sacredness, pure greed.

And so it is with the sexualized abuse of women: something precious and priceless destroyed that should be protected. We have a woman to thank for saving the last of the southern herds of buffalo, Mary Goodnight, whose husband was a cattle rancher. She had a heart for the loss of the buffalo and convinced him to catch her some calves. Mary cared for those calves and started an entire buffalo herd. I wanted to help, too, I thought, by restoring buffalo to Indian Lands, but that was a Native American issue. What I needed to have restored was my sense of self-worth.

Buffalo Medicine guided me to Houston, stampeding through a canceled concert, canceled recording session, and a long night of Shelley’s drinking so I could learn a painful truth about my family. If Buffalo Medicine is “being willing to be the answer to someone else’s prayers,” then James Swan, without fully knowing what power he had courted, had been the answer to mine despite the lawsuits and losses. Annie and Shelley had also become an answer to a prayer. My prayer has always been for healing and the buffalo’s return. And I pray, in some way, it may be that for you, too.

Crow has brought the message

To the children of the sun

For the return of the buffalo

And for a better day to come

We shall live again…

— Robbie Robertson & The Red Road Ensemble, Ghost Dance

Ghost Dance

In memory of Robbie Robertson 1943-2023

In 2016, President Obama signed the National Bison Legacy Act into law, designating the American bison as the National Mammal of the United States and declaring the first Saturday of November National Bison Day.

Paid Subscribers receive the following Premium Content below:

Ghost Dance by Bill Miller, performed by Thea & the GreenMan LIVE (unreleased).

Letting Go by Annie Hawksong with Thea on lead vocal (unreleased) is based on The Twelve Steps of Recovery.

In a House of Grey & White, a poem written by Thea at Annie’s House

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Thea Summer Deer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.